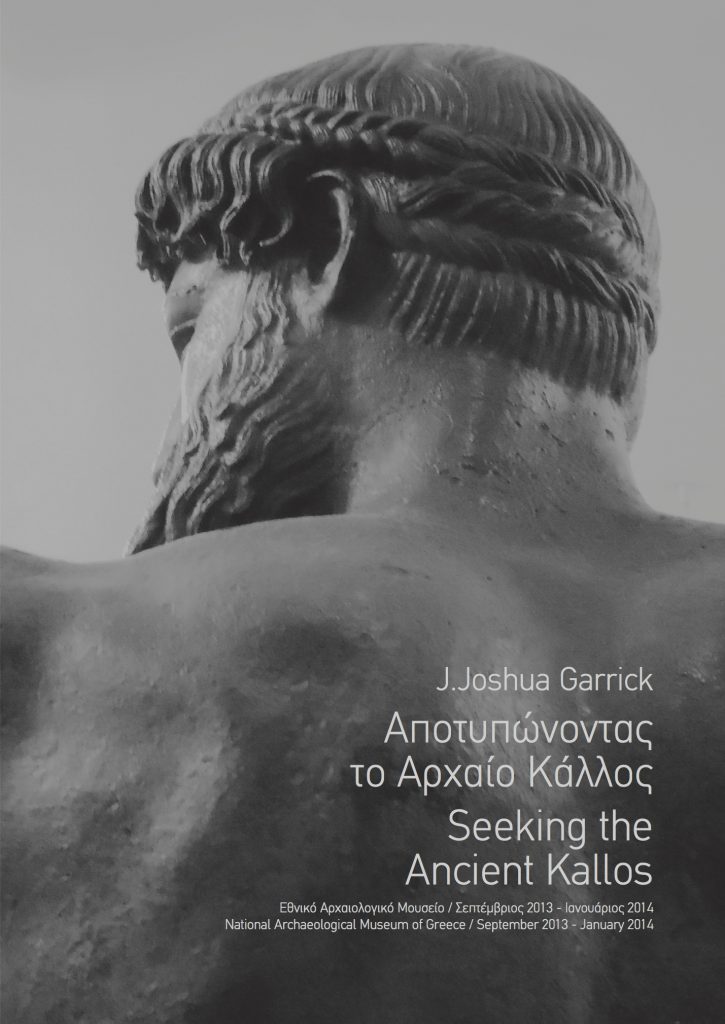

PASSION - VISION - MISSION

By Dr George Kakavas – Acting Director of the National Archaeological Museum and Director of the Numismatic Museum

(Translated in English by Matt Gkikas)

The concepts of passion, vision and mission delineate a triptych within which the idea, conception and realisation of art at the highest level are incarnated. Art that exalts love and admiration for Greece, its starting point being the ancient Greek Kallos, its messenger the creations of Josh Garrick, its final destination the National Archaeological Museum and its devotees all those amongst us who were born Greek, or consider themselves Greek.

Josh Garrick wandered like Ulysses, pursuing endlessly, endeavouring arduously and devising ingeniously in order to approach his own Ithaca, in order to conceptualise and render through his art and technique the Kallos of “classical” sculpture at its apogee. As his creations bear witness, he succeeded.

He has proven himself to be a mature master, an experienced art traveller and a humble creator who succeeded in fulfilling his lifelong dream, offering his precious wares at the “altar” of classical art that is the First Museum of Greece, the enviable National Archaeological Museum.

The unexpected angles from which Josh’s sensitive lens captures the Museum exhibits –printed on aluminum– set up a visual dialogue between the unique artist’s works and the chosen exhibits within the Museum walls, where they “live and breathe”. This gave Josh Garrick the ticket –the opportunity– to be the first non-Greek artist in the world to exhibit his work at the National Archaeological Museum.

Josh Garrick’s irrepressible passion for the pursuit of ancient Greek beauty led him to realise his vision and exhibit his photographic creations at the National Archaeological Museum, amongst the sources of his inspiration and thus accomplish his mission and fervently proclaim his love and admiration for the timeless values and the universal ideals hidden in every manifestation of ancient Greek Kallos as idea, as expression, as ideal and as creation.

I am happy as Acting Director to stand by Josh’s side and help him bring his vision to life, welcome him to exhibit his exceptional works at the National Archaeological Museum, the Museum closest to his heart.

TO SEE IN A DIFFERENT WAY … SEEKING THE ANCIENT KALLOS

by Joel Joshua Garrick

(Translated in Greek by Matt Gkikas)

“The aim of Art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” Aristotle

Growing up in farm country in America –far from the large cities which celebrate the ARTS in their museums and concert halls– my unexplained love of all things having to do with ancient Greece seemed to me, as a student, to be as unattainable as the adventures of the Star Wars sagas.

But my obsession with Greece, that innate desire to walk where Socrates and Pericles and Phidias walked, was ALWAYS inside me. If there existed a way for us mortals to question Zeus, perhaps HE could explain why I was chosen to help spread the word of the wonders of Greece. I gave up questioning WHY and have spent my adult life sharing my love and respect for that time –2400 years ago– when the greatest collection of geniuses the world has ever known walked the streets of Athens.

With scholarships and hard work, this poor farm-boy graduated from New York City’s Columbia University with a Master of Fine Arts degree. Books about ancient Greece have always been by my bed, and I have always found ways to incorporate studying its treasures while receiving my education.

My earliest work, based upon a graduation gift that became my first trip to Greece, was realistically based –or so I thought at the time– on photo-journalism. I had never seen the color blue as brilliant as the blue of the sky in Greece. I had never experienced swimming in water so magnificently clean and clear that “seeing the bottom” was taken for granted, and I had never experienced the majesty of eagles flying over Mt. Parnassus in Delphi immediately following a thunderstorm. That happened as I arrived in Delphi for the first time, and I saw those eagles and thunderbolts as a message from Zeus himself. I was finally in Greece … and I was HOME.

It was Greece –and experiences such as those just mentioned – that opened my eyes to the aesthetic potential of what could happen when I held a camera. It seems so long ago. It was a time when we had to be concerned with what would happen to our film as it passed through metal detectors at airports, but from that first trip, I experienced the unique hospitality and generosity of the Greek people, and I found myself wanting to share these wonders.

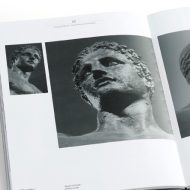

With the boldness of youth, I began to photograph the treasures of Greece –from the acropolises of Tiryns, Mycenae and Athens to the statues, sculptures, and pottery as they “live and breathe” in your great museums. Deep in my soul I knew those statues and sculptures needed to be seen in a new way –outside of the slide shows of dusty college classrooms– in order to be placed in a new context of appreciation. It quickly became my life’s work to photograph these ancient treasures and share them in every way possible: with students; in magazines; art galleries; and museums.

I sincerely hope that that which has been called my “straightforward photographic style” reveals their Aristotelian “inward significance.” Ask any student who has ever traveled with me to Greece, and they will assure you that the act of sharing my images and published thoughts reflects a very personal blend of aesthetic idealism and love for your country.

Having had a biological father who never understood my appreciation of aesthetics, I was blessed in my adult years by a series of close associations with father figures of world renown who taught and encouraged me in ways no formal education could.

The first was Sir Rudolf Bing, General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera for whom I served as an intern –after graduating from Columbia University. Sir Rudolf’s words of wisdom have guided me throughout my life. In retrospect, his words sound to me as if they could have come from Thales. One example –“In every situation, remain a gentleman.”

The second was Silas Rhodes, Founder of the School of Visual Arts, who allowed me to take on the position of Media Spokesperson for the college at a time –from the mid 1980’s through the 1990’s– when New York City’s creativity was exploding with vitality. I’ve often said, “Columbia University made me a writer and a researcher, but teaching at the School of Visual Arts made me an Artist.”

Silas Rhodes invited the most controversial Artists of the time –including photographers Joel Peter Witkin, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andres Serrano– to come to the College and speak. It was my job –and my great joy– to greet them, take them to dinner, and in some cases order the security to protect them from the often-present protesters. It was a time when ART was controversial –and I listened, I learned, I questioned, and I was emboldened by what these “renegade” Artists were printing and exhibiting.

The most important “lesson” that resonated consistently through these “guest lectures” related to the simple act of taking a photograph. Expressed with different words but with one message, it became clear to me that these Artists understood that the act of taking a photograph enhances the subject while unconsciously guiding the potential viewer as to “what is worth seeing.” In the enviable position as the guest Artists’ host, I did not have to stand in line after each lecture to struggle to ask my question. By doing my job as their host, I was in the position to put them at ease by expressing my real admiration for their work (NO Artist ever tires of that) but more importantly, they came to realize that I was no simple flatterer. I had studied their work. I de-constructed their compositions, and I asked probing questions that communicated to these Artists that I was ‘seeing’ at least some part of what they wanted the viewer to see.

Each of these legends of photography caused me to look with fresh eyes at the reverence I felt for my subject –a reverence that even today borders on religious fervor. These innovators opened my eyes to the pitfalls of that reverence. Reverence can –in some cases– enhance one’s view, but just as often it can lead to formality or even sterility. I wanted the opposite of that. I wanted my viewers to see the statues I loved as “living and breathing” in their contemporary temples called museums.

As the conversation would –on occasion– turn to what they easily recognized as my passion, they challenged me to question HOW to best photograph the works of Art of ancient Greece. Probing questions came naturally to them. They helped me realize that my obsession had to do with the fact that we cannot touch these priceless objects, but that the act of photographing them was a way of becoming one with them. Even more –by sharing my work, I was sharing that which I loved. In an epiphany of freedom I realized I not only wanted my students to see –I wanted all of America to see what I loved so deeply in the works of Art created by the geniuses who lived and worked at least 2400 years before I ever picked up a camera.

With the blessing of Silas Rhodes, and the encouragement of his sons David and Tony –who still run the College today– I created a college course called The Art and Culture of Ancient Greece, in which I led groups of American students to Greece. Finally I could immerse myself in the country, the people, and the monuments of this country which had always called to me. Over time, I have introduced the history and traditions of Greece to hundreds of Americans –and in return– I have received unprecedented access to photograph your monuments and treasures.

The first stop during those student trips would always be the National Archaeological Museum for the obvious reason that there is no other museum in the world that so exemplifies the birth and progression of the ART of Western Civilization.

I have always taught my students, “the responsibility of the photographer is to help the viewer see in a different way.” Out of respect for the Artists who created these works over several millennia, I feel an enormous responsibility to honor the brilliance and sense of pride in humanity that these works represent.

Consider the omnipresence of the camera today. No one would consider traveling or vacationing without bringing along at least one camera –even if it’s the one in your cell phone. And looking back, I was tough with my students –forbidding them to take ordinary photographs where they hand off the camera to a friend, stand in front of a building, smile and take a photo that is little more than a visual diary of a place where the bus happened to stop. With my love of Greece, I wanted my students to combine photography’s representative nature with its expressive potential. I wanted them to open their minds to the unique dignity and mysterious inner lives of the statues and monuments –all bathed in the incomparable and omnipresent Greek light.

I worked to be an effective teacher –encouraging my students to use the brilliant, and artistically inspiring, light of Greece to create compositions in shades of white, black and gray. In so doing, I came upon my own technique of focusing on details of statues and buildings, as for example, the hand of a statue or a single pillar from a temple. These details came to be my own form of “abstraction” and led to a series of pictures which brought the viewer ever closer to the image –inviting them to “see the works in a different way.”

Every American photographer studies the great Ansel Adams, who once said that when photographers create Art, they create “a statement that goes beyond the subject” and captures “an inspired moment on film.” As photography has moved into the digital age, I still believe in the “inspired moment.” Adams also said, “All the pictures I’ve done were done because I was there.” I am so happy that “I was there.” From Patras to Methoni and from the hills surrounding Sparta to the monasteries of Chalkidiki, I’ve sought “the inspired moment” throughout your country.

As the world descends into “leadership” by those who place undue emphasis on the Euro or the Dollar or the Pound, it is more important than ever for the people of the world to fully understand the inestimable “wealth” of your country. My work is to photograph the 2400 year old treasures that I’ve studied all my life. I now print those images on aluminum and hopefully provide “a new way of seeing” which reflects the culmination of a career of studying, caring for, and respecting those works of art.

It is my sincere hope that my photographs help persuade those who view my work to recognize –and value– the cultural legacy that began in Athens. It is the greatest honor of my life to bring my work home to Greece. Once again I reference Thales who reminded us that even when all else is gone, we still have hope. Please know that these photos –these subjective studies of your treasures– are here to honor your priceless gift to the world.

It is my sincere desire to help the people of Greece reach deep into Pandora’s fabled box and pull out HOPE.

Please join me. Please “see in a different way,” and proudly recall the reasons WHY GREECE will always have the wealth of its remarkable history to exhibit and to share with the world. I humbly submit these photographs of your treasures. In doing so, I ask each of us to reflect and understand how very different our lives would be today if Athens had not been “the school to the world” over 2400 years ago.